The United States and the Soviet Union spent years locked in ideological conflict as each side sought to subvert the other and spies from both sides tried to penetrate the others’ halls of power. This war was not fought solely behind closed doors in the FBI, the CIA, and the KGB.

This three part blog series will illustrate how these issues played in the American magazines, books, pamphlets, and movies of the day. Except as otherwise noted, the illustrations come from the pop culture collection of Michael Barson, the author of more than a dozen books, including Red Scared: The Commie Menace in Propaganda and Popular Culture, Teenage Confidential: An Illustrated History of the American Teen, True West: An Illustrated Guide to the Heyday of the Western and Agonizing Love: The Golden Era of Romance Comics.

The United States and the Soviet Union were not always locked in a Cold War.

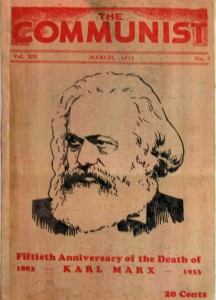

In fact, in  the 1930s the Communist Party operated quite openly in the United States. This was a period when capitalism wasn’t looking too good: the Great Depression was gripping the world and fascist regimes were rising in Europe. Though not particularly popular across the broader American society, the communists attracted a sizeable following particularly among workers, members of oppressed minority groups, and some of the intelligentsia and their literature, such as The Communist circulated freely.

the 1930s the Communist Party operated quite openly in the United States. This was a period when capitalism wasn’t looking too good: the Great Depression was gripping the world and fascist regimes were rising in Europe. Though not particularly popular across the broader American society, the communists attracted a sizeable following particularly among workers, members of oppressed minority groups, and some of the intelligentsia and their literature, such as The Communist circulated freely.

Then, during World War II, the Soviets were our allies in fighting and crushing Nazi Germany. Joseph Stalin became the friendly “Uncle Joe” and books such as Ambassador Joseph Davies’ Mission to Moscow appeared lauding the Soviet Union, its economic and social progress, and its contribution to the war effort. Mission to Moscow was not only a bestselling book, with some 700,000 copies sold, but it also became a Hollywood motion picture.

One commercially successful movie that argued for close relations between the United States and the Soviet Union was Song of Russia, a 1944 film in which Robert Taylor plays  an American conductor who is touring the USSR and who falls for and marries a Russian girl whom he realizes is “just like an American girl.” Their romance is interrupted by the Nazi invasion and Peters helps set his wife’s town on fire to deny it to the Nazi invaders. The film ends with the message that “We are soldiers, side by side, in this fight for all humanity.”

an American conductor who is touring the USSR and who falls for and marries a Russian girl whom he realizes is “just like an American girl.” Their romance is interrupted by the Nazi invasion and Peters helps set his wife’s town on fire to deny it to the Nazi invaders. The film ends with the message that “We are soldiers, side by side, in this fight for all humanity.”

That was precisely the picture stirringly portrayed on the cover of Time Magazine on May 14, 1945.

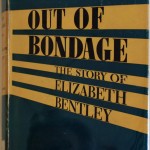

Things were about to change drastically, however. In 1946, Soviet military intelligence code clerk Igor Gouzenko defected in Canada and publicly discussed the extent of Soviet espionage in North America. Then in 1948, Elizabeth Bentley, an American communist who had left the party in 1945 and told the FBI everything she knew, went public with her claims about the oppressive atmosphere within the Party and the espionage committed by American communists on behalf of the USSR.

Around the same time, American intelligence started being able to read encrypted cables  sent during the war by Soviet intelligence officers in the United States, a project that ultimately became known as VENONA. In this way, the Government gained hard but extremely secret evidence confirming and expanding on the claims made by Gouzenko, Bentley, and others. Propelled by these and other alarming developments, the ground shifted and the Government began vigorously pursuing Communists, particularly those in positions of trust.

sent during the war by Soviet intelligence officers in the United States, a project that ultimately became known as VENONA. In this way, the Government gained hard but extremely secret evidence confirming and expanding on the claims made by Gouzenko, Bentley, and others. Propelled by these and other alarming developments, the ground shifted and the Government began vigorously pursuing Communists, particularly those in positions of trust.

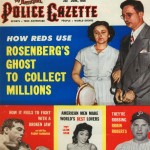

Some of the accused Americans were convicted of espionage and related crimes or of violating the Smith Act. Most famously, Julius and Ethel Rosenberg went to the electric chair for their role in selling the atom bomb secret to the Soviets. Others merely had their reputations dragged through the mud. Many of the people who came under scrutiny did have communist connections; some actually were guilty of espionage. Others however, fell into neither category. Whatever their fate, few went quietly.

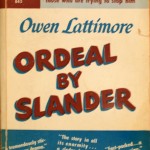

The National Police Gazette even imagined the Rosenbergs’ ghosts plaguing the country. Other people, like Owen Lattimore, a professor of Asian Studies at Johns Hopkins University whom Senator Joseph McCarthy once accused of being “the top Russian espionage agent in the United States,” fought back in the court of public opinion.

The National Police Gazette even imagined the Rosenbergs’ ghosts plaguing the country. Other people, like Owen Lattimore, a professor of Asian Studies at Johns Hopkins University whom Senator Joseph McCarthy once accused of being “the top Russian espionage agent in the United States,” fought back in the court of public opinion.

As they watched parade of accused government officials, professors, movie stars, and just plain folks across their TV screens and newspaper headlines, many Americans across the country became concerned that a senseless witch hunt was under way.

Not privy to the VENONA secrets and rightly suspicious of the methods of Senator Joseph McCarthy, some Americans argued that the threat of Soviet espionage was a phantasm, a hoax perpetrated on the American people by the FBI, McCarthy, the House Un-American Activities Committee and others.

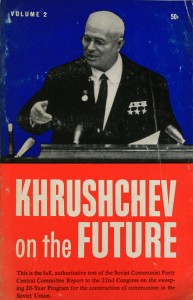

It wasn’t clear to the American public at the time, but the Government’s continuing counteroffensive against the Communists had pretty much broken the back of the Communist Party in America by the mid-to-late 1950s. The Party continued sputtering along—indeed it still exists today—but it was increasingly irrelevant to real American life and in doctrinaire fashion it continued pumping out turgid prose about the merits of the Soviet Union…books that nobody read.

It wasn’t clear to the American public at the time, but the Government’s continuing counteroffensive against the Communists had pretty much broken the back of the Communist Party in America by the mid-to-late 1950s. The Party continued sputtering along—indeed it still exists today—but it was increasingly irrelevant to real American life and in doctrinaire fashion it continued pumping out turgid prose about the merits of the Soviet Union…books that nobody read.

Part One of a Three Part Series

By Mark Stout and Michael Barson