December 15, 2010

Mark Stout, SPY Historian

Everyone knows that the United States Government has been flying spy satellites for some fifty years. The government declassified the CORONA program in 1995 and we all saw pictures of the Soviet Union that had long been TOP SECRET. But how did the government’s imagery analysts use these pictures? And what happened to the film that intelligence analysts pored over fifty years ago?

In an effort to answer these questions, my colleague Dan Treado and I visited the National Archives at College Park for a look at some of their remarkable holdings dealing with satellite reconnaissance. The records that we saw were once kept in vaults at classified facilities. Now they are in the stacks at the National Archives and though we got a special dispensation for a behind-the-scenes visit, they can be retrieved for any researcher who wants to work with them.

When we arrived, two archivists led us into one of the Archives’ several cavernous storage rooms containing declassified records. Here we found the actual canisters containing the film that the imagery analysts of CIA’s National Photographic Interpretation Center (NPIC) worked with.

CORONA film canisters. The black pen marks strike through their original classification markings.

Photo: Dan Treado

What’s on these rolls of film? Of course, there were images of the ground, as you might expect. Early on, however, a “horizon camera” was added to take an additional picture of the arc of the Earth with each image of the ground. This second image helped analysts determine precisely where the main camera was pointing.

The CORONA program (and the short-lived related ARGON and LANYARD programs) ended up producing some 2.1 million feet of film containing some 866,000 images.

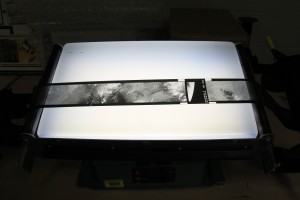

This is a huge amount of film and that in itself created a major challenge. Imagine, for instance, that an analyst is sitting at a light table analyzing an image of the Soviet Union and he or she wants to know when a particular building was built. In order to answer that question, the analyst will need to look at older images. Clearly, plowing frame by frame through the mountain of CORONA film looking for the right images is not an option. What to do?

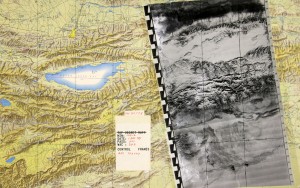

The CIA had a clever solution which the National Archives has faithfully preserved. The Agency took a set of maps covering the entire world and pasted on them copies of each of their images, printed to the same scale as the maps, and augmented with reference data allowing retrieval of the film. An analyst wanting to find earlier imagery of a particular target would only have to go to the appropriate map, see what was pasted on it, and then retrieve the indicated canister of film. (In fact, this is the same process that an historian wanting to use the film at the Archives would go through today.)

A map next to its corresponding CORONA film. Kyrgyzstan is to the north and to the south is The People’s Republic of China.

Photo: Dan Treado

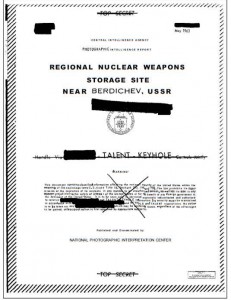

With the proper imagery at hand the analyst could write up a report that would go to policymakers and other analysts. Though we did not look at them on this trip, many of these reports are available at the Archives on the CIA’s CREST database. Samples can also be found in the CIA History Staff’s fine volume on the Corona program.

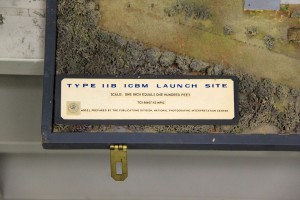

The CIA put Corona imagery to other uses, as well. Sometimes analysts or policymakers found it helpful to see in three dimensions what the satellite images showed. For this purpose, NPIC maintained a model shop. Sadly, most of the models were flimsy to begin with and they have not aged well. In fact, only two of the models are in the National Archives, though a few may be populating display cases and book shelves at CIA and other agencies. Today we’ll show one of them. A future blog post will feature the other.

The label on this model shows what it is:

And here it is in all its glory:

The modelers made these pieces to an exacting level of detail. Here we can see the representation of the Soviet ICBM launch apparatus.

We shall never see the likes of such models again. Today such models would probably be made virtually in a computer. However, we are fortunate that the outstanding professionals who work at National Archives have saved these models and all the other Corona records for the benefit of historians and through them for all of us. In the National Archives, the American taxpayer is getting a good deal.