The Cold War was a period of fear in the United States. Not only did the threat of nuclear war loom over the country but there was a feeling that Communist subversives could be anywhere. During the first half of the Cold War in particular, there were “reds under the bed.”

In fact, so fervid was the anti-Communist imagination that is seemed the very cosmos itself was under threat. Saturn Science Fiction and Fantasy magazine ran a non-fiction article about the alarming prospect of a “Red Flag over the Moon.” “The Man in the Moon will be broadcasting down to Earth every day—in Russian. That’s the way it’s probably going to be,” the article warned. The only solution was that “rocket men must speak out and name their objective boldly and clearly. We want the moon! We want it now, and we want it for the free world!”

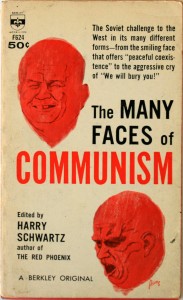

The transition from Joseph Stalin to the arguably less menacing Nikita Khrushchev as leader of the Soviet Union and the head of the international Communist movement did little to diminish concern among anti-Communists. The publishers of even a relatively sober book such as The Many Faces of Communism (1962) found it advantageous to use cover art portraying Khrushchev as looking alternately demonically cheerful and apoplectically enraged.

In the face of this alarming threat, there was a class of people who made it their purpose in life to eradicate Communism and its twin threats of subversion and espionage. Many of these anti-Communists were themselves refugees and converts from left-wing politics. Others were professional spy hunters and law enforcement personnel. Some were driven to make whole careers out of combating the Communist menace. They often found themselves derided as “professional anti-communists,” the implication being that by hyping the threat, they lined their own pockets by ensuring further speaking engagements and book contracts.

One such professional anti-communist was Jacob Spolansky who had come to the US from the Ukraine during the early 20th century. During World War I he spied on radicals in Chicago for the War Department’s Military Intelligence Division. In 1919, he started a 30 year career working for the FBI hunting members of the International Workers of the World (so-called “Wobblies”) and communists before retiring and writing his gripping memoirs, The Communist Trail in America which came out in 1951, wrapped in a bold red dust jacket.

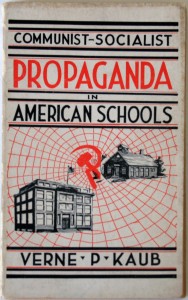

Many anti-Communists feared that the tide of history might be running in favor of the Communists if for no other reason than the Communists were steadily infiltrating the American educational system, corrupting American youth who would be the next generation of American leaders.

An organization which made it its mission to battle communists was the National Council for American Education (NCAE), launched in 1948. The NCAE first made a splash with its 1949 opus Red-Ucators at Harvard which it followed with How Red is the Little Red Schoolhouse? The cover of its 1953 book Communist-Socialist Propaganda in American Schools portrayed American schools caught in a Bolshevik web. In essence it was an attack on the National Education Association, the teachers’ union, and its alleged inculcation of Communist values. The author of this work was Verne P. Kaub, the NCAE’s head of research. A Wisconsin newspaperman and religious activist, he had flirted with leftist politics himself, being for a time a member of the Socialist Party of Michigan, before making an ideological U-turn. Before joining the NCAE he had combated communism in the Congregational Church and then in the Tennessee Valley Authority.

The U.S. Government itself was on the case, of course. In particular, the FBI was there to protect the American people and subversion and espionage. The FBI did this by, among other things, infiltrating groups all across American society, ranging from the PTA to the civil rights movement to ensure that Communists were not taking them over from within. Hoover himself wrote (ghostwrote, more likely), three books including the 1958 Masters of Deceit: The Story of Communism in America and How to Fight It, the 1962 A Study of Communism which sold an amazing 125,000 copies in hardcover and the 1969 J. Edgar Hoover on Communism.

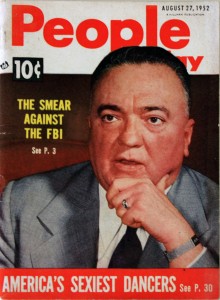

Hoover was not the only one blowing Hoover’s horn. There were a great many unquestioning, even hagiographic treatments of the Bureau and of J. Edgar Hoover in the popular media, as well. Even comic books such as Calling All Boys and Treasure Chest promoted Hoover and his communist hunting efforts. He was also a favored cover model for magazines such as True Detective and the National Police Gazette. True Detective offered its readers “A Day with J. Edgar Hoover,” while the National Police Gazette, in article by a former aide to the Chairman of the House Committee on Un-American Activities (known as HUAC) said that Hoover could be proud of his enemies, “especially the members of the criminal Communist conspiracy, together with their pseudo-liberal allies and dupes.” For instance, on August 27, 1952 the front cover of People Today plugged the story “The Smear against the FBI,” just above a banner urging readers to turn to an article about “America’s Sexiest Dancers.” This article defended Hoover and the FBI against its detractors by arguing that the Bureau was suffering from a backlash against its own publicity which had “over-glorified and over-glamorized” the Bureau and its Director.

Meanwhile, a spy war was going on across the world and in the pages of American popular literature…