During the Cold War the American public had an endless appetite for information and entertainment about the menace from the Soviet secret services. Nazi spies had never really lived up to their promise and the Nazi regime had been rapidly snuffed out of existence, but Soviet spies were everywhere, or so it seemed, and they showed no sign of going away. Publishers, especially of mass market paperbacks, rushed to satisfy this demand.

Judging purely by the tone of titles, it could sometimes be hard to tell the difference between the fiction (Don’t Betray Me and The Devious Defector) and the non-fiction (Crime without Punishment and Elizabeth Bentley’s Out of Bondage). The fiction could be quite lurid both in language and in subject matter. W. J. Saber’s 1967 novel The Devious Defector starts out with a Bulwer-Lyttonesque line: “The wind howled along the Fredreichstrasse, driving the snow before it in streaks of white knives.” Saber’s editors apparently never noticed that he had managed to misname one of the most famous streets in Berlin. Mickey Spillane’s 1951 novel, One Lonely Night, had Mike Hammer going under cover to combat Communists supported by Soviet intelligence who are bent on taking over the United States. Sitting through a Party meeting, our hero engages in revenge fantasies:

Gladow spoke. The aides spoke. Then the General spoke. He pulled his tux jacket down when he rose and glared at the audience. I had to sit there and listen to it. It was propaganda right off the latest Moscow cable and it turned me inside out. I wanted to feel the butt of an M-1 against my shoulder pointing at those bastards up there on the rostrum and feel the pleasant impact as it spit slugs into their guts.

The non-fiction could be equally lurid. Matt Cvetic was the author of a series of articles in the Saturday Evening Post entitled “I Was a Communist for the FBI” which later became a radio serial and a movie. In his book The Big Decision: The Story of Matt Cvetic, Counterspy (1959), quoted Comrade Leon, an American Communist leader as saying in a Party meeting, “when the Communist Revolution starts in the United States, I’m sure as hell going to enjoy torturing and butchering the clergy and tossing their bodies into the Ohio River.” Guenther Reinhardt recounted an incident from his service as a member of the Army’s Counter Intelligence Corps in which he was forced by naïve superiors to return to Soviet custody—and sure torture and execution—a Russian intelligence officer who had defected to the American zone. The Russian Captain keeps trying to escape so that he can be shot while escaping, but he is repeatedly thwarted: “Two CIC agents and one of the Constabulary sergeants jumped on him. The [Russian] Captain threw them all off shouting ‘kill me, kill me.’…It took five men to hold him and a blackjack to subdue him.”

Both the heroes and the villains of these works deal in moral absolutes. They believe that when fighting an absolutely evil enemy, any measure is justifiable. Even Mike Hammer, one of the American good guys feels this way. At one point in One Lonely Night he strips a woman naked and whips her because he believes she is a Communist. Ironically, he later comes across a good American woman stripped naked and being beaten by the Communists. (The book’s cover art alludes to this scene.) This violation of female American flesh enrages him so much that he shoots everyone in sight. In the middle of his rampage, he has an epiphany: “I was the evil that opposed other evil, leaving the good and the meek in the middle to live and inherit the earth.”

Hammer’s view may have seemed extreme, but it was different only in tone from the words of a major government report on the future of American intelligence written in 1954 by a commission headed by World War II hero General Jimmy Doolittle:

It is now clear that we are facing an implacable enemy whose avowed objective is world domination by whatever means and at whatever costs. There are no rules in such a game. Hitherto acceptable norms of human conduct do not apply. If the US is to survive, longstanding American concepts of “fair play” must be reconsidered. We must develop effective espionage and counterespionage services and must learn to subvert, sabotage and destroy our enemies by more clever, more sophisticated means than those used against us.

Many characters—fictional and otherwise—were willing to make moral compromises in order to defeat the Soviet enemy who was even worse. In 1963, however, John LeCarre, came out with one of the greatest spy novels of all time, The Spy Who Came in from The Cold, which cried a loud “a pox on both your houses!” LeCarre, himself a veteran of British intelligence, drew a sharp distinction between the free West and the enslaved East, but he saw no moral distinction between their intelligence services. For him, espionage was inherently a debasing activity.

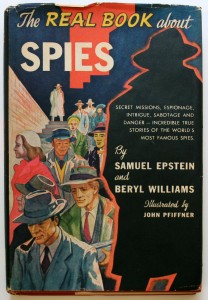

LeCarre would probably have been appalled at the thought that espionage was meanwhile, becoming a matter for children seeking career options. The contents of the 1953 Real Book About Spies may have been thrilling: Nathan Hale, “The Young Saboteurs of the Churchill Club,” “Klaus Fuchs and the Atom Bomb Spies,” and more. However, the book’s dust jacket art conveyed a decidedly different message, portraying earnest-looking but friendly men (almost all men) in gray suits, and the hats that were de rigeur at the time, apparently walking to the office.

Ironically, this cover is probably more truthful about the real nature of the intelligence business. Spillane, Cvetic, Doolittle and LeCarre notwithstanding, in the United States it had become the realm of company men laboring in large bureaucracies.

By Mark Stout and Michael Barson