Legendary British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher (October 1925 to April 2013), who would have turned 89 this month, was convinced that Britain’s intelligence services should remain absolutely secret, and tried repeatedly to protect them from the gaze of public scrutiny. Her philosophy was – in her own words – ‘Never admit anything unless you have to’.

Legendary British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher (October 1925 to April 2013), who would have turned 89 this month, was convinced that Britain’s intelligence services should remain absolutely secret, and tried repeatedly to protect them from the gaze of public scrutiny. Her philosophy was – in her own words – ‘Never admit anything unless you have to’.

An avid reader of Frederick Forsyth thrillers, she was fascinated by the magic and mystery of the secret services. In the words of her Chancellor, Nigel Lawson, she was ‘positively besotted’ by them. Indeed, she would be the first Prime Minister in history to attend a meeting of the Joint Intelligence Committee, Britain’s senior intelligence assessment body, since its formation in 1936.

Her deep respect for the intelligence agencies led her to believe that their activities should never be disclosed to the public. As leader of the Opposition, she was horrified by the Labour Government’s decision in 1979 to approve the publication of Volume I of Sir Harry Hinsley’s official history of British Intelligence in the Second World War. Before publication, she wrote to the Prime Minister, James Callaghan, expressing her ‘disquiet at the prospect’.

Whereas Callaghan and others in government saw the history as a good opportunity to showcase British intelligence achievements during the war, including the work of codebreakers at Bletchley Park, Thatcher adhered to the classic argument that intelligence agencies should never celebrate their successes, and never explain their failures. ‘I was taught a very good rule by my Masters at Law’, she wrote, ‘never admit anything unless you have to; and then only for specific reasons and within defined limits’. She continued: ‘It is a rule that has stood me in very good stead in many a complicated matter, and in the absence of further advice I should be inclined to stick to it now’.

Thatcher was informed that the Central Intelligence Agency had endorsed the Hinsley project, to which she responded cynically ‘In view of the treatment meted out to their own intelligence service, I have little confidence in their judgement on publication matters’ – a damning verdict on the Agency’s failed attempts in the 1970s to prevent ‘dirty tricks’ from coming to light.

In office, Thatcher’s desire to preserve intelligence secrecy was resolute, leading to confrontation and embarrassment. In 1980, she was so appalled by an imminent Panorama documentary on the UK intelligence services that she seriously considered using the government’s seldom-used power, inscribed in the BBC’s charter, to veto programmes. In a handwritten note she pointedly commented: ‘I would be prepared to use the veto’. The veto option was rejected on the grounds that it would generate a ‘tremendous hoo-ha about censorship’, and instead the Cabinet Secretary, Robert Armstrong, was sent to put private pressure on the Direct-General of the BBC, Sir Ian Trethowan, who (as a scribbled note in official files indicates) was considered ‘weak’ by Downing Street. Efforts to persuade Trethowan to cancel the programme ultimately failed, although the government did manage to censor parts of the broadcast version.

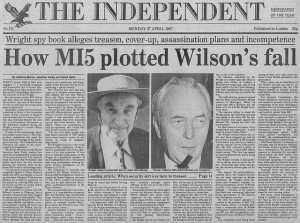

No episode better illustrated Thatcher’s determination to keep intelligence services secret than the so-called ‘Spycatcher Affair’. The affair concerned the government’s attempts to suppress the memoirs of Peter Wright, an embittered former Assistant Director of MI5, which contained allegations that the late Roger Hollis, a former MI5 Director, had been a Soviet spy.

In a move that backfired spectacularly, Thatcher attempted to halt the book’s publication in Australia but lost, with the judge ruling that Wright’s ‘revelations’ were neither new nor damaging to national security. In the Sydney courtroom, the hapless Robert Armstrong, who had been sent to make the government’s case, was ridiculed for refusing to acknowledge that MI6 existed and harangued for stating, in a priceless admission, that it was sometimes necessary for a person in his position to be ‘economical with the truth’. Thatcher’s ill-fated crusade against the book ensured that it became a global bestseller; the affair was confirmation that secrecy can be a two-edged weapon.

Thatcher, who left office in November 1990, was the last Prime Minister to subscribe to the view that the intelligence services should be walled off completely from public view. This antediluvian mindset faded in the 1990s, as her successor John Major introduced the Intelligence and Security Committee and publicly admitted the peacetime existence of MI6, and was firmly laid to waste by Tony Blair, who took the unprecedented step of publicizing intelligence material to make his case for the invasion of Iraq.

–by contributing author Dr. Christopher Moran, Warwick University, author of Classified: Secrecy and State in Modern Britain.