Master storyteller Ben Macintyre’s most ambitious work to date brings to life the twentieth century’s greatest spy story with A Spy Among Friends: Kim Philby and The Great Betrayal. Macintyre is a writer-at-large for The Times of London and the bestselling author of Double Cross, Operation Mincemeat, Agent Zigzag, The Napoleon of Crime, and Forgotten Fatherland.

Master storyteller Ben Macintyre’s most ambitious work to date brings to life the twentieth century’s greatest spy story with A Spy Among Friends: Kim Philby and The Great Betrayal. Macintyre is a writer-at-large for The Times of London and the bestselling author of Double Cross, Operation Mincemeat, Agent Zigzag, The Napoleon of Crime, and Forgotten Fatherland.

He recently spoke with SPY’s historian and curator Dr. Vince Houghton to discuss A Spy Among Friends, Kim Philby’s legacy, and the treacherous double-crossing actions of espionage throughout the Cold War.

Vince Houghton: There have been many books written about Kim Philby, what makes this book unique?

Ben Macintyre: My decision to write anew about Philby rests on two principal considerations: The last major biography of Philby is now almost 20 years old, and in the intervening time a huge amount of new material has come into the public domain, most recently diaries of MI5 counter-intelligence chief Guy Liddell. Moreover, individuals connected to the story have become far more willing to talk about it.

The Philby story has always been told as an ideological tale, the clash of two opposing superpowers. As the Cold War recedes (and another threatens) I wanted to write the story through the prism of character, personality and individual motivations, rather than just politics.

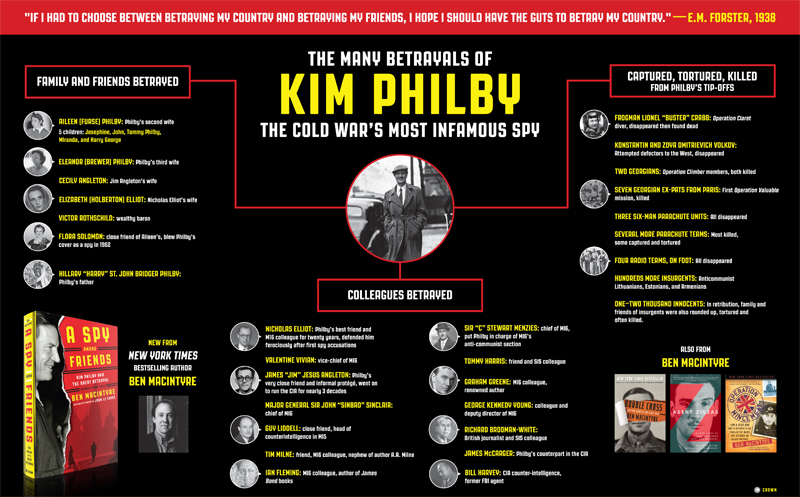

VH: This book seems to be as much about Nicholas Elliott as it is about Kim Philby. Despite his historical revisionism regarding his suspicions about Philby (asserting he had some suspicions long before he obviously did), Elliott comes across as an exceptional intelligence officer, particular considering his prescience about the post-Cold War world.

BM: Elliott was in many ways a brilliant, highly professional officer, which makes Philby’s betrayal all the more poignant. Like all spies (including Philby) he went to great lengths to muddy the waters afterwards. He had an uncanny ability to see the big picture clearly, while being utterly blind to the real political situation in his own backyard.

VH: Philby’s reputation as a master spy is somewhat dampened by the fact that he needed considerable luck – on several occasions – to avoid discovery. Is this a fair assessment?

BM: All spies need luck. But Philby’s good fortune was truly uncanny. Time and again, he came within a whisker of exposure, and got away with it. That said, he also knew that his luck would run out in the end, and always had an escape plan in place.

VH: The relationship between Philby and Jim Angleton is fascinating. On one hand, Philby trained the greatest CIA counterintelligence officer in history. On the other hand, Philby’s betrayal caused Angleton’s demise.

BM: Undoubtedly, Philby’s relationship with Angleton did more damage to western intelligence than any other single factor. Angleton was a brilliant fool, one the cleverest people in the business of intelligence, who was utterly duped, and then entirely warped by the experience. Philby helped to create Angleton, and then drove him to madness.

VH: It’s hard not to feel some admiration, or maybe even sympathy, for Philby. As your book’s subject, did you grow more or less admiring of Philby as you wrote the book?

BM: The strange combination of ruthlessness and charm, and the tension between these sides to his character, is what makes Philby so fascinating. I ended up despising him – for his arrogance and brutality – but lost in admiration for the way he had pulled it off. Years after he defected, even some of those he had betrayed most cruelly, could not bring themselves to repudiate him. Having spent so long living with the ghost of Philby, I feel the same.

VH: How much of a role did McCarthyism play in the time it took British intelligence (or at least MI-6) to finally begin to accept Philby’s potential guilt?

BM: There was a feeling within MI6 that Philby was being made a scapegoat for a youthful left-wing dalliance. This was compounded by a determination that the McCarthyite witch hunts taking place in the US must not be allowed to happen in the UK – and Philby was seen as a test case, in part, for British tolerance and liberalism, away of proving, ironically, that Britain was less paranoid about communism than the US.

VH: Miles Copeland said that Philby did so much damage to both US and British intelligence during the period 1944-1951 that we would have been better off doing absolutely nothing. Could there be a greater indictment of Philby? Or perhaps the better word would be veneration?

BM: Copeland was one of those whose fury at what Philby had done was matched by admiration at his achievement. His extraordinary achievement was not just to tell Moscow what the west was doing, but also what MI6 and CIA were thinking of doing; this enabled the Soviets to plan ahead of the enemy’s planning in a way that no intelligence organisation has ever been able to do before.

VH: John Le Carré writes in the afterward that he had a chance to sit down with Philby in the 1980s but passed on the opportunity. He didn’t want to give Philby a platform. As a historian, would you have taken the opportunity to sit down with someone like Philby? I suppose the analogous situation would be a historian’s willingness to sit down with Aldrich Ames or Robert Hanssen.

BM: I would love to have sat down with Philby (and Ames and Hanssen for that matter). I can understand why Carré passed on the chance – he had, after all, been a serving officer himself, and the betrayal was still quite raw in the 1980s. But spies lie, and particularly lie about (and to) themselves. I would have given anything to sit opposite Philby, look him in the eye given all that I now know about him, and ask him why he did it?

VH: The most obvious question: Did Elliott allow Philby to escape?

BM: My belief is that, in the end, Philby was allowed to flee. The door to Moscow was left wide open. Elliott left Beirut, having extracted the partial confession from Philby, and left no surveillance in place. He could not have made it easier for Philby to run. The last thing anyone in MI6 wanted was a public trial in the UK. They wanted the problem to go away. I think it was calculated that Philby, like Burgess and Maclean, might just fade into obscurity behind the iron curtain – if so, it was major miscalculation. The key piece of evidence in this is Philby’s own belief that he had been pushed, rather than jumped, revealed in a hitherto unpublished letter sent to Elliott soon after Philby arrived in Moscow. In this, Philby wrote that he had come to believe Elliott wanted him to do a “fade”, spy jargon for a defection.