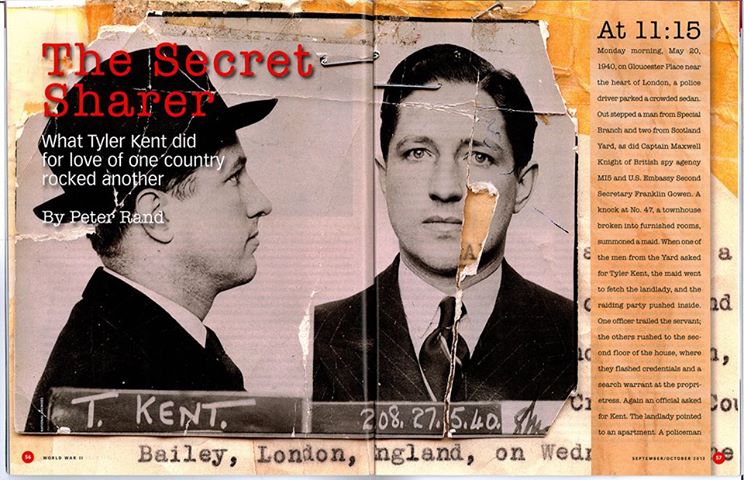

Tyler Kent’s Secret Plot against FDR, Churchill, and the Allied War Effort

How a handsome young American diplomat stole thousands of secret documents and nearly changed the course of World War II in this gripping story of espionage, love, and international intrigue.

How a handsome young American diplomat stole thousands of secret documents and nearly changed the course of World War II in this gripping story of espionage, love, and international intrigue.

A black sheep with diplomatic privilege, Tyler Kent stood at the crossroads of history: Stalin’s purges, the rise of Hitler, and the Phony War. Author Peter Rand discusses how he weaved together Kent’s star-crossed love affair, imprisonment, and trial into a rich tapestry that conveys a fresh vision of the tumultuous era.

Q&A with Peter Rand

Q: Where was the story of Tyler Kent born? What prompted you to write a book about Kent?

A:I first heard about Tyler Kent when I had lunch one day with Howard Gotlieb, the head of the Boston University Special Collections, now called the Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center. Howard had acquired Kent’s papers, and hadn’t shown them to anyone until he spoke to me about them because he’d agreed to wait until Kent had died. I teach at Boston University, and I’ve given them my manuscripts, and Howard was a friend of mine. So he told me about the archive, and once I started reading the Kent papers, I decided to write the book. You can’t walk away from a story like this one.

Q: You traveled to Moscow and London to research the book. Can you elaborate on some of your more memorable discoveries?

A: The fifty handwritten love letters Kent kept written to him during the war when he was in prison and she was in London. They are rich in detail and feeling and she describes scenes during the V1 and V2 bombings that take you back to that time. Also the Kent evaluations written by Ambassador Bullitt and others were memorable. Letters are key to historical narrative, to telling a personal story. But I also found very fine material at the Public Record Office in Kew outside of London recently released by M.I.5, and these included some real curiosities, such as notes between top British officials concerning how to handle the Kent case. Then in Moscow I was able to visit places Kent used to frequent, including Spaso House, home of the U.S. Ambassador in Moscow, where in 1934 Bullitt gave parties attended by Stalin’s old Bolshevik cronies, almost all of whom were liquidated in the next few years. I visited the Hall of the Nobles where the Show trials were held.

Q: Tyler Kent came from Staunton Virginia, and many references are made to the “Southern” contingent of influencers to FDR who seem to fall out of favor during the course of the book. Was the treatment of Tyler Kent tied to that outcome, and if so, how?

A: Kent was not treated badly for that reason at all. But by the time of his arrest most of the old family friends he knew had retired, except Cordell Hull, who distanced himself even from Kent’s mother. That’s what was shocking – how badly the State Department and Hull treated Kent’s mother, Annie Patrick Kent, whose husband had served in the Consular Corps for a quarter of a century, and who had been reduced by circumstances to running a boarding house on Wyoming Avenue. When she sought help for Kent, from Roosevelt, Hull and others, they wouldn’t see her or answer her letters. It aged her many years to go through the ordeal.

Q: Politicians are often manipulating public opinion in the run-up to wars. Do you think that Kent’s archive would have been able to keep America out of World War II?

A: Maybe. That’s because if it had come to light that Roosevelt was violating the spirit of the Neutrality Act he might not have been able to run for a third term, and Churchill might well have been forced to resign if people had discovered that he was negotiating secretly with Roosevelt behind the back of Neville Chamberlain, the Prime Minister, when he was First Lord of the Admiralty. Many people in England were opposed to Churchill’s determination to wage all-out war with Hitler. A great many Americans opposed intervention in the European war. All that changed after Pearl harbor, but people tend to forget how things stood in those early days. Kent’s archive could have changed the political dynamic and, subsequently, America might not have gone to war. We’ll never know.

Q: Can you talk about Tyler Kent’s motivation? He obviously resented his lowly stature, and must have enjoyed the attention that his possession of the documents generated, but what was the main driver to his actions?

A: He wanted recognition. I think that was a driving force. It was partly vanity. He had a grudge, a chip on his shoulder, as a Southerner who thought he deserved to be one of the hot shot young diplomats in the State Department. Instead, he was a clerk. He wanted people to think he was important. And then he began to sense the import of all those purloined documents he took home, including the Churchill-Roosevelt telegrams. He began to feel that he could influence history. He really did believe that American diplomats wanted to get the U.S. into the war, and he hated the interventionists. He was genuine in his political convictions. And he got recognition – that’s the irony. He was a hero to the isolationists – at least for a time. Some people thought he was a martyr.

Q: So many recent books have been written about Joseph Kennedy lately. In your research, did you discover any surprising facts about him during the time of his Ambassadorship?

A: Just wonderful diary entries about the inner workings of power and his gripes about Roosevelt and Churchill. It was surprising to discover, for example, that he was irritated when Churchill offered him a whiskey and soda. He was offended that Churchill didn’t know he was a teetotaler. He told Churchill he’d stopped drinking for the duration of the war. I was not surprised to discover that Kennedy knew how to cut corners and make quick, expedient decisions. But he comes alive in those pages of personal, private expression.

Q: Did you find out something about Tyler Kent or any of the other main characters that was a surprise? Did you learn anything that was not part of the historical record?

A: Otto Jahnke’s claim that Tyler Kent was part of his Nazi/Soviet spy network

had not been part of the historical record when I found it in recently released files of M.I.5. Irene’s wartime letters to Tyler Kent had never been read by anyone aside from Kent until I found them in his archive. I was surprised to discover the degree of anti-Semitism that existed in the State Department and how poor security was in the Moscow Embassy and even in the London Embassy.

Q: What similarities do you see between Tyler Kent and Bradley Manning, the source of the documents that were released to Wikileaks? Were they both solo players with a specific goal in mind?

A: Bradley Manning and Tyler Kent were both troubled young men who acted alone because they wanted to expose what they considered unacceptable secret practices of the government to which they had unusual access to documentation. They acted with mixed motives. There is always a need for recognition, or self-exposure, in people who act on their own in a way that draws attention to them. It’s a compulsion partly created by an intolerable alienation.

Q: To what do you attribute the spate of new books about World War II?

A: People have more distance now from that time, and they are not as emotionally committed to the great players and a sense that in order to be great you have to be a great man or woman in every way. What people want to know is how figures in this time of war handled themselves and others. That’s one reason. Another reason is that the Second World War, and these leaders, shaped the times we live in now – times that are committed to war and nationalism and territorial claims, to the power game. People have begun to question this approach, and the system, and the way the system makes decisions that affect the lives of people in this country. This is part of a new approach to film and television by younger filmmakers who do not see everything in terms of good vs. evil – good people do bad things dept. At the same time, people look back at the thirties and early World War Two as a romantic, vanishing time. But they will always go back to revisit this story. It’s in our blood. We go back to Shakespeare constantly to find new meaning. We go back to King Lear and Richard the Third because we keep discovering new ways to understand power and its effects. We will revisit Churchill and Roosevelt and Stalin to understand who we are.

Q: Are you going to write another WWII book or will you go back to fiction?

A: I am working now on the story of Virgilia Peterson, an American writer, and her marriage to Prince Paul Sapieha, a Polish prince. They lived through the 1930s in Poland, and watched the rise of Hitler, and had to flee when the Germans invaded. It’s a great story and through that vantage point a new way to tell it. I have done a great deal of research on their life in the 1930s and in wartime in Europe and America.