History is a tricky thing. And it turns out that we here at the International Spy Museum had part of it wrong. Our only excuse is that a lot of other fine institutions had it wrong, too, including NPR, the US Army, and the Library of Congress. But what we had wrong is an interesting story.

We had an incorrect photograph on display. We thought that it was a picture of a spy named Mary Bowser. It is an often-told story that an African-American woman named Mary Bowser worked as a slave in Confederate President Jefferson Davis’ White House and from that vantage point spied for the Union. Mary Bowser was an intelligent woman who did spy for the Union using the role of servant or slave as cover. She passed the information she acquired to Elizabeth Van Lew, her employer and benefactor, a white woman of high social status in the Confederate capital of Richmond, Virginia. Van Lew, an important spymistress, in turn, passed the information to the Union Army. Despite popular belief, there is no evidence that Bowser actually spied in the Confederate White House, a claim neither she nor Van Lew ever made, but a great story, and one that stands in for all the truly dangerous spying and intelligence gathering she did do in the Confederate Capital.

We had an incorrect photograph on display. We thought that it was a picture of a spy named Mary Bowser. It is an often-told story that an African-American woman named Mary Bowser worked as a slave in Confederate President Jefferson Davis’ White House and from that vantage point spied for the Union. Mary Bowser was an intelligent woman who did spy for the Union using the role of servant or slave as cover. She passed the information she acquired to Elizabeth Van Lew, her employer and benefactor, a white woman of high social status in the Confederate capital of Richmond, Virginia. Van Lew, an important spymistress, in turn, passed the information to the Union Army. Despite popular belief, there is no evidence that Bowser actually spied in the Confederate White House, a claim neither she nor Van Lew ever made, but a great story, and one that stands in for all the truly dangerous spying and intelligence gathering she did do in the Confederate Capital.

Mary Bowser was a natural for our museum. First, she represented the class of women—and there were many—who broke into the predominantly male domain of espionage during the Civil War. Second, she represented the legions of African-Americans who were not content to be acted upon by history, but who chose to be agents of it.

There is a photo of Mary Bowser that circulates widely. You see it attached to this story. NPR used it on their website in 2002 when they did a story on this Civil War Spy. The US Army used it when they inducted Bowser into their Military Intelligence Hall of Fame. We got our copy from the Library of Congress and put it in our exhibit on Civil War intelligence.

Well, along comes Lois Leveen, who last year published an historical novel entitled

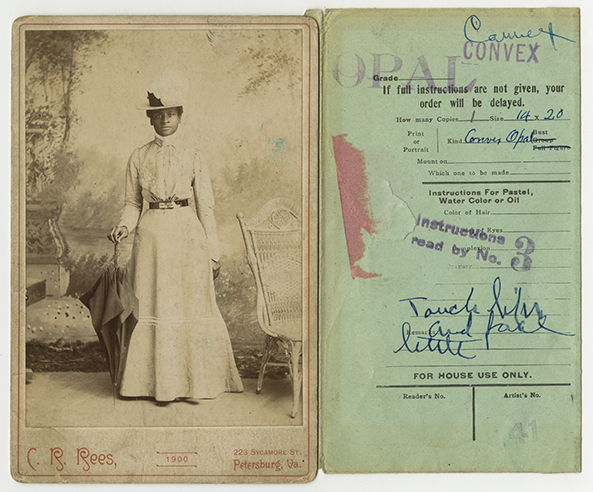

The Secrets of Mary Bowser. Her publisher had wanted a picture of Ms. Bowser so she had dutifully provided them a copy of the photo, but she always felt a little uneasy about it. With the issue tugging at her conscience, she employed the “great triumvirate of historical research,” by which she means “diligence, doubt, and dumb luck.” This led her to the original photograph at The Library of Virginia just a couple months ago.

In an article published on June 27 in The Atlantic Leveen describes how she held the original photograph in her hand, admired the face of the young woman in it and looked at the date on the card stock to which the photo was affixed: 1900. The spy Mary Bowser would have been about 60 years old in 1900. This woman was clearly much younger. So, it turns out that we don’t know what one of the most audacious spies of the Civil War looked like. For years everyone, including the International Spy Museum, has been redistributing in generation copies of a photograph of a Mary Bowser but not the Mary Bowser.

This sort of thing is not uncommon in the history business. It’s always worth re-examining what we think we know. New historians going over the same ground will come up with new and more compelling interpretations or they will ask new questions of an old subject. Sometimes they will even discover that the raw facts aren’t facts at all. It is possible that this problem is particularly prevalent in the field of intelligence history. In any event, the past is always in flux.

We have removed the erroneous photograph from our exhibit. Mary Bowser’s face remains hidden in the shadows of history. For a spy, that seems fitting. Here’s to you, Mary, wherever you are. And thank you Lois Leveen, for doing the double-checking that other institutions, including us, did not do. Well done.

–Mark Stout

International Spy Museum Historian

Great piece. Making a note to put that novel featuring Mary Browser on my list. Currently reading Mrs Lincoln’s Dressmaker, based on the story of Elizabeth Keckley or Keckly, who was Mrs L’s modiste for a long time, including during the Civil War. Also, Keckley published her own memoir. Apparently there was a fuss for some time about whether she actually wrote it, but that doubt was effectively subdued.

Pingback: Spying: The Secret History of History | elcidharth

Well done, Mr. Stout and well-written. What a great opportunity it was to reflect on how history is told/created/uncovered. I am glad you did not hide the (understandable) error, but rather used it for everyone’s benefit. And congrats to Ms. Leveen as well.